As planetary demises go, this one is pretty grisly: a planet falls closer and closer to its host star, getting hotter and hotter as it spirals inward, until it finally falls past the point of no return and is swallowed by the star in a tremendous flash of light. That’s what happened in an event called ZTF SLRN-2020, and now the James Webb Space Telescope has been observing the aftermath to learn more about this rare event.

“Because this is such a novel event, we didn’t quite know what to expect when we decided to point this telescope in its direction,” said lead researcher Ryan Lau of NOIRLab, who used Webb’s MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument) and NIRSpec (Near-Infrared Spectrograph) instruments to make observations. “With its high-resolution look in the infrared, we are learning valuable insights about the final fates of planetary systems, possibly including our own.”

Astronomers had originally thought that the planet was destroyed when the star swelled up and engulfed it. But now, with the new data, they think that the planet spun inward toward the star until it was swallowed.

“The planet eventually started to graze the star’s atmosphere. Then it was a runaway process of falling in faster from that moment,” said researcher Morgan MacLeod of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. “The planet, as it’s falling in, started to sort of smear around the star.”

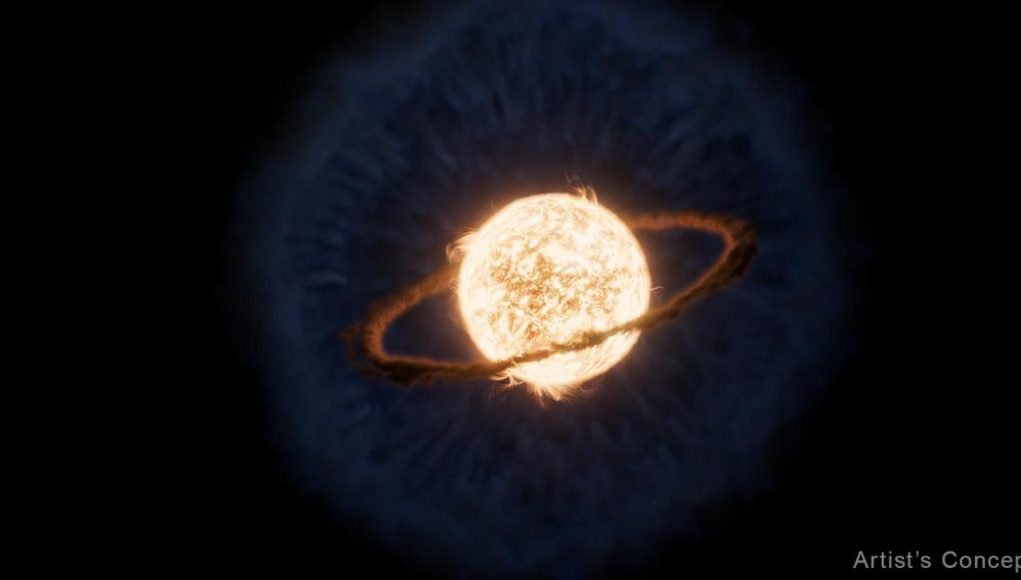

When the planet finally fell in toward the star, it splashed away layers of gas from the star’s outer atmosphere, and this gas gradually cooled into cold dust which now sits as a cloud around the star. Within this cold dust, there is a smaller disk of hot gas closer in, which includes carbon monoxide.

“With such a transformative telescope like Webb, it was hard for me to have any expectations of what we’d find in the immediate surroundings of the star,” said researcher Colette Salyk of Vassar College. “I will say, I could not have expected seeing what has the characteristics of a planet-forming region, even though planets are not forming here, in the aftermath of an engulfment.”

It’s extremely rare to find an event like this, but the researchers are hoping they will be able to observe more similar events in the future, using both Webb and upcoming telescopes like the Vera C. Rubin Observatory and NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope.

“This is truly the precipice of studying these events. This is the only one we’ve observed in action, and this is the best detection of the aftermath after things have settled back down,” Lau said. “We hope this is just the start of our sample.”

The research is published in in The Astrophysical Journal.